Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The gathering on a late summer’s day at the Chinese Embassy in Canberra early last year was not meant to be about diplomacy.

Xiao Qian, the newly appointed Chinese ambassador to Australia, was hosting his first event as Beijing’s emissary to honour a NSW senior constable who died while trying to rescue a Chinese student in the Blue Mountains.

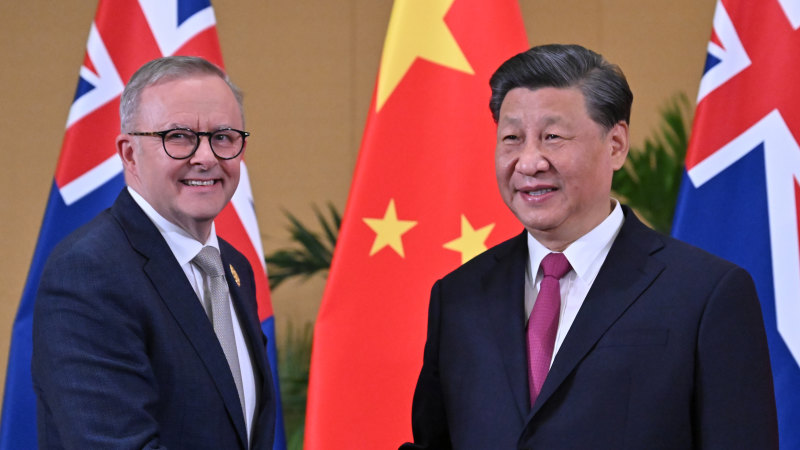

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is set to visit China and meet President Xi Jinping.Credit: Illustration: Dionne Gain

Between presenting the parents of Kelly Foster with a Great Wall Commemorative Medal in recognition of their daughter’s courage, Xiao took the opportunity to send a message to the Australian government that it had not heard in more than two years.

“China is willing to work with Australia to meet each other halfway,” he said.

More than 18 months after Xiao was sent by Beijing to try to revive a relationship that had spiralled through trade strikes, diplomatic freezes and disputes over human rights and national security, Anthony Albanese will arrive in China on Saturday for the first official visit of an Australian prime minister in six years.

In between there has been a change in government in Canberra, the release of Australian journalist Cheng Lei from arbitrary detention and relief from $20 billion in trade strikes.

The Labor government has given ground too, most recently allowing Chinese company Landbridge to keep its lease over the Port of Darwin. It has also resisted imposing Magnitsky sanctions on Chinese officials over human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

In Beijing, Albanese will meet China’s Premier Li Qiang and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People. It is the highest-level meeting that can be granted to an Australian prime minister, but while both sides are relieved to be on the way to halfway, they are not there yet.

“This is not a relationship that is the same as it was in 2016,” said one senior official in Canberra, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss diplomatic matters. “It is not a journey back to the future.”

Much of the legwork leading up to Albanese’s visit has already been completed. The winding back of trade sanctions on industries like wine and barley was needed to publicly lock in the visit, and so too was the release of Cheng Lei.

But five key issues will dominate the next steps: China’s pitch to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership, critical minerals, Xi’s meeting with US President Joe Biden next week and the domestic political environments of both China and Australia.

Trading times

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, otherwise known as the CPTPP, is verbose and in need of a rebranding – but it is one of the world’s largest trade agreements and Beijing wants in.

China, as the world’s second-largest economy, sees it as its right to join the trade deal to open up markets across the Pacific. Others are not so keen. After years of economic coercion from China, Japan has made it clear it does not see a future for China in the deal.

Australia, after weathering $20 billion in trade strikes, has suddenly softened its tone. In October last year, Trade Minister Don Farrell said there was “no prospect” of China joining the deal. But last week the South China Morning Post reported Canberra would “not oppose” the trade pact bid.

“They will advocate for their own entry, and we will talk about the high standards required,” said one senior Australian government official. Asked directly if there was a nuanced position of not supporting but not opposing, the official said did not go into any more details. “Our position has already been articulated.”

Importantly for Beijing, discussions about its own membership have dominated Taiwan’s own bid to join the giant trade pact. The newfound stability in the relationship between Australia and China means it is unlikely that Canberra will now turn around and support Taipei’s bid.

“China has two goals for the CPTPP,” says Kevin Magee, a career diplomat, former Australian ambassador and representative in Taipei.

“One is to keep Taiwan out. The other one’s to get themselves in. Those are equally important.”

Albanese has repeatedly claimed the relationship between Australia and China is not transactional.

“They just don’t like to say it is because then all sorts of trouble [comes] from the opposition and the media and elsewhere,” says Magee. “Generally, a lot of things are just done on a quid pro quo and deniable basis. Both sides have wounds they can lick.”

How critical are critical minerals?

Very critical, it seems. In March, as the spirit of stabilisation was in full swing in Canberra and Beijing, Treasurer Jim Chalmers blocked China’s Yuxiao Fund from increasing its investment in Australian rare-earth miner Northern Minerals. “We’ll need to be more assertive about encouraging investment that clearly aligns with our national interest in the longer term,” he said.

The resources are used in everything from lithium batteries to high-end military equipment. Australia has some of the world’s largest supplies of these minerals, but China dominates the production that transforms them into usable quantities.

As with Australia’s exports of iron ore, that would usually be a complementary relationship, but Washington has made it clear to Canberra that it wants more critical minerals being produced in the United States and elsewhere.

“From Beijing’s perspective, Australia’s alignment with the United States signifies a departure from the complementary relationship in the critical minerals supply chain,” said Marina Yue Zhang, an associate professor at the University of Technology, Sydney, in research published by the Lowy Institute.

Australian ambassador to the US Dr Kevin Rudd and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in Washington DC last month.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

“The prevailing sentiment in Beijing is that Australia is, once again, being used by the United States as a ‘pawn’ in its strategic competition against China.”

Don’t be surprised to see a small but symbolic concession on critical minerals in Beijing.

The bigger picture

Albanese’s visit is important, but it is just a prelude to the meeting that will happen between Xi and Biden the following week in San Francisco.

The Australian government has resisted being tagged as a go-between for the two superpowers, but the timing is irresistible. Albanese will arrive in Beijing a week after being hosted by Biden at the White House for a state visit.

One ambassador to Washington, Lui Tuck Yew, of Singapore, who also previously served in Beijing, characterised the US-China relationship like this: “mutual suspicion, intractable issues (and) an absence of strategic trust”.

Australia’s ambassador to the United States, Kevin Rudd, who completed a doctorate on Xi Jinping Thought at Oxford University, told the Council on Foreign Relations that he believed Xi wanted to change the relationship in “a direction more accommodating of Chinese interests and values” while the US had “embarked on a conscious campaign of economic derisking from China” – making their relationship more volatile.

“We need to be realistic about these strategic underpinnings,” he said.

Albanese’s task will be to encourage more open communication lines, particularly between the country’s two militaries, which have grown dangerously strained in the past year.

On the home front

Xi has had a tumultuous few months by his own standards. He sacked his foreign minister in July after suggestions of an affair with a reporter, then his defence minister Li Shangfu in October amid a corruption probe.

On Thursday, he attended the memorial service for his former premier, Li Keqiang, who died at 68, only months after leaving office. The sudden death of the relatively liberal leader has triggered scenes of mourning across the country, some of it targeted at the more authoritarian rule of Xi.

Albanese’s official visit to the Great Hall of the People, like Xi’s meeting with Colombian President Gustavo Petro and Californian Governor Gavin Newsom last week, allows China to reset the narrative to project stability and prestige in a lightly unbalanced domestic political environment.

“It will be portrayed on [Chinese state media service] CCTV as being Australia reconciled with China coming to show its respects to a great power,” says Magee.

Residents mourn for the late former Chinese premier Li Keqiang in Zhengzhou city.Credit: AP

Back in Canberra

Talkback radio has a useful shorthand for travelling prime ministers. In 2007, there was “Kevin 747”, and now there is “Airbus Albo”.

Usually, it inflicts minimal damage on leaders from a public that is aware that travelling is part of the job. But the failure of the Voice referendum and the soaring cost of living has put some domestic political pressure on Albanese after trips to Washington, then Beijing in the same week, with the Cook Islands and San Francisco soon to follow.

Australian officials have been keen to reframe part of China’s trips to a domestic audience. Particularly on Sunday, when Albanese will spend a good chunk of the day speaking with Australian agriculture producers in Shanghai at the China International Import Expo.

They are also managing expectations about the trip overall. It is unlikely we will see Albanese walking along a People’s Liberation Army line in Tiananmen Square, as other leaders have done, which would create challenging optics and provide fresh material for Coalition MPs who argue Labor is going soft on China.

“If a country is going to be a serious player in the region, you have to travel,” said Magee. “Because otherwise you’ll be ignored.”

Get the best of Good Weekend delivered to your inbox every Saturday morning. Sign up for our newsletter.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article